Birds of the British Empire

Residency Season: Summer 2020

Birds of the British Empire is a work-in-progress by James Coupe, developed as part of his Synthetic Media artist residency at Thoughtworks Arts. Mining British colonial archives, literature and historical records, it uses AI and machine learning systems to reconstruct an aviary of (para-)fictional birds. The morphology, identity and description of each bird is unique, emerging directly from specific colonial texts: one bird is generated from Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, another from Baden Powell’s Scouting for Boys, another from CLR James’ The Black Jacobins, and so on. The birds in this aviary mimic the logic of empire by privileging the unique traits of rarity, otherness and exoticism. At the same time they also create an alternative archive, one in which identities and narratives that have been historically erased, altered and ignored can be recovered, leading to more emancipatory futures.

The training sets used in machine learning systems are, like colonial archives, artificially constructed bodies of knowledge that encode and reinforce historical processes of cultural domination such as otherness, surrogacy, displacement, and erasure. Over the course of his residency at Thoughtworks, Coupe has been working with various Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), datasets and source materials. Birds of the British Empire involves many separate, interrelated automated processes to create its aviary of deepfaked birds, alongside an algorithmically generated ‘Field Guide’ that describes these birds through the prism of the colonized lens.

Archives are never neutral. More than simple repositories of information, archives are indexes of a society’s changing ideological investments and political commitments. Bias and subjectivity are constitutive, not incidental, to the construction of an archive, which is not a naturally occurring resource so much as an artificially constructed body of knowledge, one that by definition treads the line between evidence and fantasy, fact and fiction.

On the surface, the archive seems firmly rooted in the historical past. By contrast, an emerging field like Artificial Intelligence looks, even lurches forward into the future. One major flashpoint in the discourse around AI is so-called “synthetic media,” a catch-all term for images, video and audio that are artificially produced, manipulated and modified by way of AI and machine learning algorithms. As a side-effect of the anxiety surrounding “fake news,” synthetic media tends to inspire moral and existential panic: when an algorithm authors a text or image without human intervention, it is viewed as a threat—not just to the notion of artistic creativity, but to the boundaries of human-centric culture more broadly. In this sense, AI provides a perfect scapegoat for problems created by human beings themselves.

Coupe’s recent work (for example, Warriors, below), uses synthetic media, particularly the algorithmically authored images known as “deepfakes,” to explore the representational dilemmas raised by processes of cultural domination such as gentrification, surrogacy, displacement, and erasure. This work builds upon his earlier explorations of surveillance. Like surveillance media, synthetic media is observational, but also inherently archival, since it originates in datasets that have been curated and organized according to set classifiers, demographics, and statistics—all of which determine value.

As an artist who often authors their work through code, Coupe is interested in unpacking the perceived threat posed by AI and understanding its basis in the curiously para-fictional status of the archive. Birds of the British Empire examines the archival basis of AI by focusing on the hidden role of datasets and training sets – in other words, the images, videos, audio, text that machines learn from. The biases, gaps and blind spots of these datasets are reproduced and amplified when we use AI to generate synthetic media from them—and this process, in turn, demonstrates the determining power of the archive in knowledge production. Synthetic media shapes how we see and understand the world by manipulating archives as a raw material for extraction, classification and optimization. As such, synthetic media should be viewed as an extension of the logic of colonization.

The relationship between the colonial gaze and earlier representational technologies – like maps, the printing press, and photography – has been described by media theorists such as Ariella Azoulay, who describes the camera shutter as a “synecdoche” for the system of imperialism itself. Synthetic media takes this further, using large datasets that flatten and reinforce socio-political differences and intensify hierarchies of power and control. In a post-automated society, whoever controls and authors the archive controls how we understand reality.

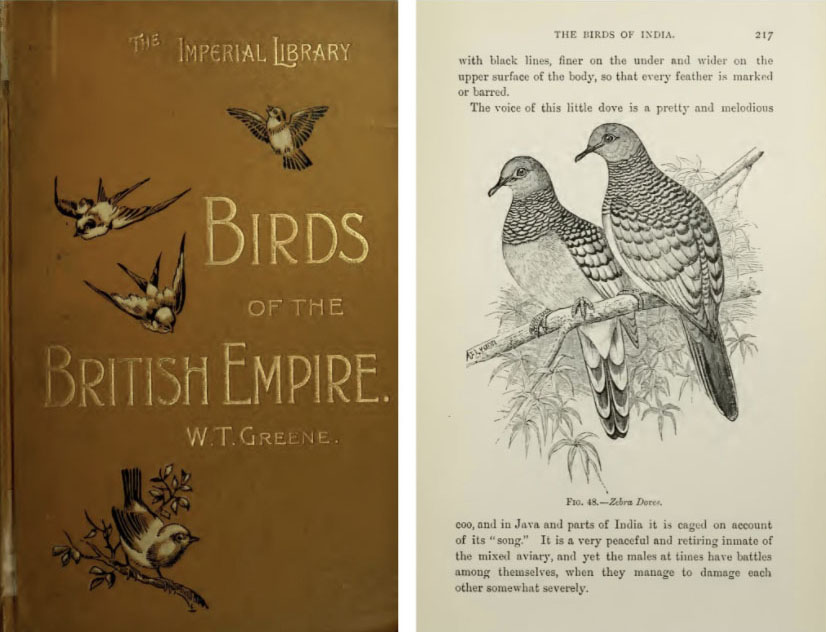

In 1898, W.T. Greene published a book, Birds of the British Empire, a taxonomy of birds native to Britain, Australia, India, and parts of North America and Africa. Many of these birds were brought to Britain, and either released into the wild, or kept in aviaries and zoos. This is part of a historical pattern of empire which was justified through the collection, colonization and classification of “others”. The birds in Greene’s book are a dataset that has provided definitions of British identity for more than a century: Browning wrote about the Song Thrush (“Oh, to be in England”). The Budgerigar, native to Aboriginal Australia, became a popular pet in working-class British homes. The Peacock, native to India, remains a common status symbol in British stately homes. These birds are an archive of empire, and cannot be adequately classified through morphology alone. They represent a way of seeing and organizing the world, and are focal points for the colonial gaze.

Greene’s birds are real, but his classification of them as an archive of “British” birds imposes a series of fictional constructs upon them. The wealth of available literary and patriotic references to this group of birds reinforce a pattern of human conquest, control and domination – over both nature and other people. In this project, Coupe and his collaborators are building a machine learning system that, using a training set of images of Greene’s birds, and other literary, archival and historical references to birds that occur in British colonial archives, synthetically generates images and videos of synthetic birds. The resulting birds, encoded with and making visible the cultural logic of empire, will be exhibited as an aviary of artificial, “exotic” birds, each with a name derived from the terms that were used to generate them. In the resulting installation, grids of video monitors, masquerading as vitrines, each contain a bird moving around and able to respond to the presence of gallery visitors: an archive that returns our gaze. Each vitrine is accompanied by a printed page from a synthetic “field guide”, with AI-authored descriptions of the birds.

Working with machine learning systems allows us to dissolve seemingly fixed cultural hegemonies into new configurations and new possibilities. This project imagines alternative classificatory and evaluative systems, and asks us to interrogate, rather than valorize, our imperial histories. It is an urgent response to the current wave of nostalgic, isolationist politics, with its nationalist mantras of taking back control, closing borders, and making things great again. Synthetic media is characterized by its grassroots, open-source origins, and it is crucial that this particular cultural technology be employed to challenge notions of linear historical and social progress, and to point at potential new paradigms for considering narratives of race, gender, class, exclusion, inequality and empire.

Work on the Birds of the British Empire project is ongoing. The team has published elements of the project’s process relating to a cloud-based Machine Learning workflow and the Continuous Integration (CI) development practice. These notes and the code which has been open sourced by the team help other artists to create their own related ML toolkits using a similar workflow.